How can you improve your company velocity, quality of decisions and employee engagement? It sounds difficult, but there’s an easy way. All you have to do is give up control.

“What the —?” I hear you ask. No really, I’ve seen it done effectively many times. Just push decision making down in the organization. Let those who are closer to the action make decisions. High performers are excited by the opportunity. And why wouldn’t they be? They have more skin in the game.

Often you can see symptoms of dysfunctional decision making creep into a startup as it scales. People are confused about how decisions get made. Or maybe they don’t feel they have the authority to make decisions. So everything gets escalated to the executives or founders. Guess what? You’ve created a bottleneck that slows everything down. If you’ve got a line outside your door, or emails stacked up seeking approval, it’s time to delegate more decisions.

Unfortunately, it takes work to get there. You can’t wave a magic wand and improve decision making over night. You need to train the organization, especially front-line managers, to make decisions. And you have to trust them to make the decisions for which they’ve been hired.

Establish Guard Rails

Good decisions must reflect the goals and values of the company. So if people are confused about priorities, like how to treat customers, what to ship, how to hire, then your’e asking them to navigate the waters without a map or compass.

Clear values and priorities establish the guard rails for good decision making. Early in my career, I had a skeptical view of company values. In larger companies, they are often generic and divorced from the day-to-day operations. But when you have clear values in a startup, that’s a powerful force for ensuring everyone is moving in the same direction.

Most decisions require tradeoffs. How much risk are you willing to take on shipping a new feature? Should you test more? Or make resources available to fix problems after release?

Values help establish the ground rules on how to make those trade-offs. Are you the kind of company that goes the extra mile for customers? Great. Make sure you live it. Even when it’s difficult. Especially then. There’s no better way to undermine the values than by backing down under pressure. Employees can see if the values are real or just window dressing.

Who Makes The Decision?

You must be clear about who makes the decision, who has input and who is merely informed afterward. While there are some fancy frameworks like DACI (Driver, Approver, Contributor, Informed), don’t make things more complicated than necessary. Be clear about who owns the decision, the time frame and what you’re trying to solve for.

For example, when you’re hiring a new employee, who makes the final call? Is it the hiring manager? Or a committee vote by the interview panel? The manager’s VP? HR?

In general, the decision maker should be the person closest to the situation and who lives with the decision on a day-to-day basis. In the case of hiring a new employee, many people are impacted, but the hiring manager lives with the consequences every day. Therefore, they make the decision. Everyone has input, but like the pig and the chicken at a bacon & egg breakfast, the chicken is involved, but the pig is committed. (Or as we used to say at MySQL with a level of Finnish pessimism, the decision maker should be “whoever gets the blame when things go wrong.”)

When To Delegate

The key to scaling a high-performance organization is the development of a strong middle management layer. Your front line managers need to be able to make high quality decisions within their area of responsibility quickly without the need to escalate for approval.

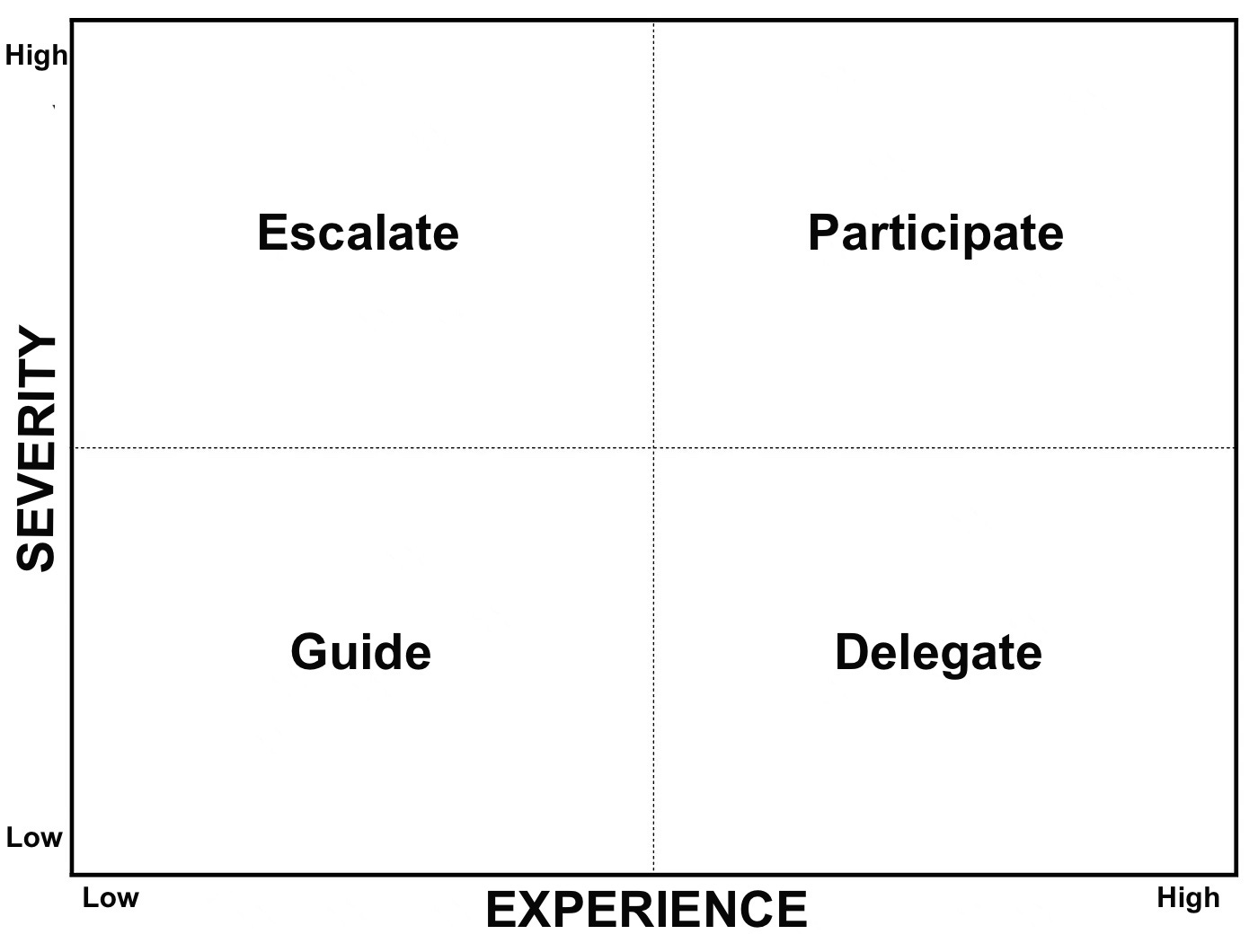

There’s a model of management called Situational Leadership developed by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard. When I learned this technique in a management workshop, it opened my eyes to understand when to delegate, when to guide, when to overrule. It made me a better manager.

While not every situation in life can be turned into a 2x2 matrix, a lot of the anguish about when to delegate can be resolved by taking into account the experience of the individual and the severity or stakes of the decision.

A routine decision, such as how much to spend on google ad words as part, should be in the wheel house of an experienced marketing manager. If they’ve done it before and are up-to-date, they likely know more about it than their manager. You might put some guard rails around the budget and set a target ROI so you can measure the results and learn. But this is a good example of a high experience / low severity situation, so it is easily delegated.

A more severe situation, such as the development of a communications strategy for dealing with a crisis, would have higher stakes and likely be outside the experience of a front-line manager. Such a low experience / high severity decision would be a good candidate for escalation to a VP or C-level executive.

A low-stakes decision where the employee doesn’t have much experience can be used as teaching moment. In cases where it’s a high stakes decision where the employee has relevant experience, you should work through it together and jointly decide.

So how do managers get experience with the more complex decisions?

Learn By Doing

You must train people to make decisions. The only way to do that is to force managers to make decisions. Start with the lower stakes decisions and then over time give them more decision making as they get comfortable.

As a C-level executive, it is quite curious to me the kinds of decisions that people would routinely escalate. Where should we hold the offsite meeting? Who should be invited? What are the topics we should discuss? What should we serve for lunch?

While it’s easy to have an opinion on everything you’re doing a disservice to your team if you make routine, low-stakes decisions. It’s like keeping your team in training wheels.

I have found the words “I trust your good judgment” to be the best answer when someone asks me to make a decision that I think they should make. (It’s also better than saying “I don’t care.”) Often they will weigh the alternatives out loud trying to anticipate what I think is best. But I make it a policy of not weighing in, so that they can develop their decision making skills.

For more complex decisions, it can be helpful to be a sounding board for someone who is not entirely comfortable with making a decision. Again, I try very hard not give an answer. If you’ve giving them the freedom to make a decision, you must trust them.

I’ve seen founders undermine the delegation process by saying “it’s your call, but it’s not the decision I would make.” Argh!

If you think someone is going down the wrong path, you should be able to frame your concern by reinforcing company values or quarterly objectives.

At Duo Security, hiring managers always made the final decision on candidates. For several years, I met every final candidate before the decision was made. And I would give my honest and sometimes harsh letter grade feedback.

When managers were under pressure to hire quickly, they would sometimes compromise on the previously agreed level of experience required. That was easy to point out without undermining their authority. In a few cases, I highlighted what I saw as mediocre performance or lack of consistent track record. In the cold light of day, most hiring managers knew that they were compromising their standards and they chose to cut the candidate loose and keep looking.

Not every decision that gets delegated will be the one you would have made. So you must be willing to tolerate some amount of mistakes. Ideally these are non-fatal and can be reversed later, if necessary. That doesn’t mean you should accept mediocre performance, but that’s a whole other discussion.

I never overruled a hiring manager’s decision. But I remember disagreeing with two hires made by Ash Devata, the head of Product. Ash was closest to the process and I trusted his judgement. There were final candidates for two different roles. One of the candidates was Wendy Nather, who was moving from an IT analyst firm to lead our Advisor CISOs. I’d seen other industry analysts move to vendors without much success and this made me uneasy. That was my own personal bias and not a view that Ash shared. The other candidate, whom we’ll call Ralph, had only a few years of experience and was interviewing for a product role.

Ash made the case for both candidates. I raised my concerns and asked him to consider what plans he would put in place to ensure they were each successful. It was Ash’s team and he had the responsibility of managing them and so it was his decision to hire them or not.

Wendy turned out to be superb. Within 30 days, it was clear she brought a tremendous level of security expertise to the company. She had huge credibility with CISOs and was able to develop high quality content that resonated with our audience. She was the kind of A+ employee you hope for. Ralph, on the other hand, failed to live up to expectations and was let go some months later.

By letting Ash make the decisions, we ended up with a stronger team. Both of us had the benefit of living with and learning from his decisions.

Getting Comfortable Being Uncomfortable

Startups are a wonderful laboratory for learning to make decisions without having perfect information. Because, let’s face it, you never have enough information.

While it can be helpful to get advice from your board or more experience executives, you have no choice but to get comfortable making uncomfortable decisions. There are very few decisions which can’t be undone. If you make a mistake, acknowledge it and fix it. When things don’t work out, learn from it and improve. You cannot hit home runs without striking out once in a while.

If you find yourself stuck on a decision, try to determine what’s preventing you from moving forward. Often it’s helpful to talk through a decision with a coach or advisor.

Sometimes I see people caught up in the optics of a situation. That is, they are worried about “how it will look” if they make a certain decision. This is a bad way to manage. It means you’re operating from fear rather than conviction. You must focus on how things are, not on how things look.

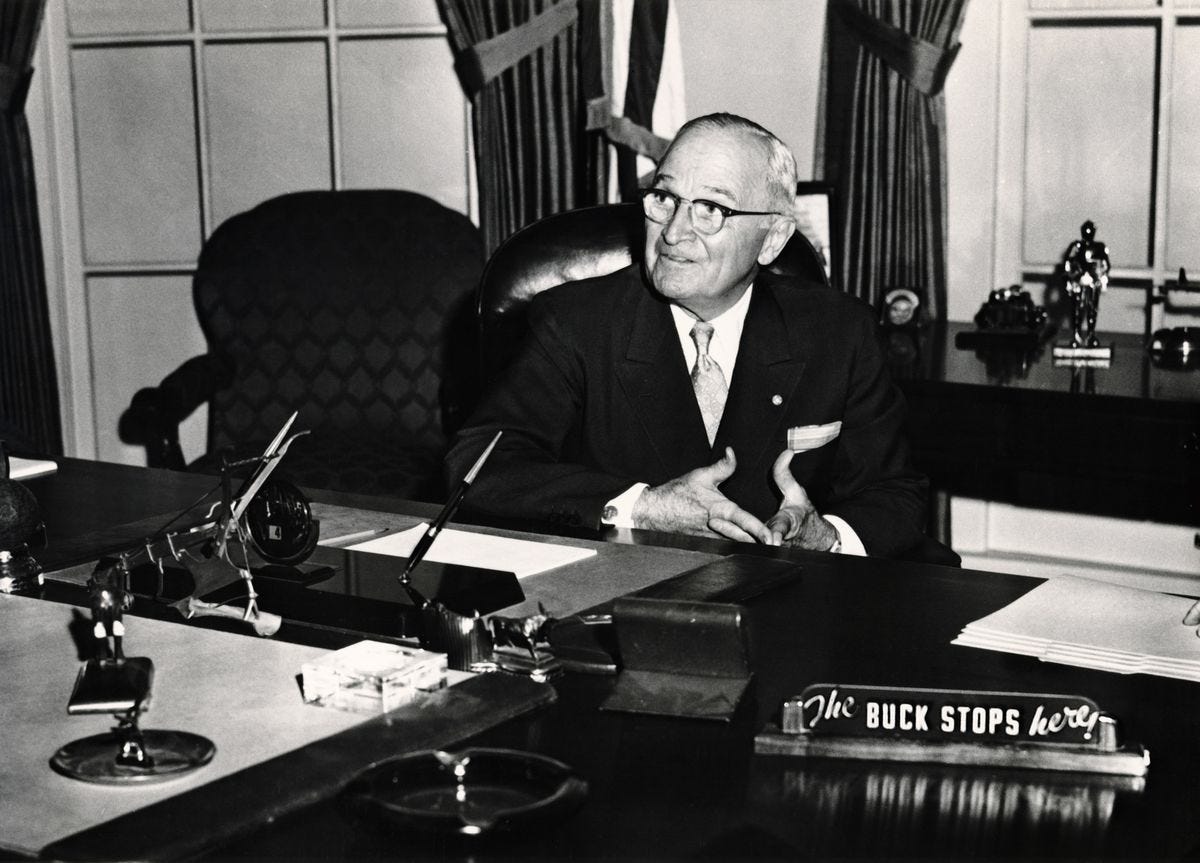

When the stakes are high and you know some of your constituents will be angry, it is tempting to kick the can down the road, to set up a committee, to stall. But making no decision, is in itself a decision, though usually not a good one.

Leadership is not easy and it often requires making very difficult decisions. For decisions which carry a lot of emotional baggage, your conviction must come from doing the best you can to serve your constituencies, including customers, employees and shareholders. At those moments, you must look to your own north star, your personal values, to guide you. If you know what you stand for, it is much easier to do the right thing.

You must be willing and able to explain your decision to those who might disagree. People may not like the decision, but hopefully they understand and respect the logic that got you there.

Hey Zack this is a great article! Awesome meeting you at the scale event!